Down Syndrome

Today is World Down Syndrome Day so we thought what better time to talk about Down Syndrome?

We would like to start by wishing the Down’s Syndrome Association a very Happy 50th Birthday! They do amazing work to support families, carers, health and education professionals. Here is a link to their website https://www.downs-syndrome.org.uk.

World Down Syndrome Day is a global awareness event…and we need you to help spread the word in your part of the world. You can help by wearing brightly coloured, mis-matched socks. Wear them at home, nursery, school, college, university, work, play, travel, on holiday…wherever you are and whatever you’re doing today the 21 March!

Make sure to take pictures and videos and post them on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram using the hashtags #LotsOfSocks, #WorldDownSyndromeDay and #WDSD20.

What is Down syndrome?

Approximately one baby in every thousand in the United Kingdom is born with Down syndrome and there are approximately 40,000 people in the UK with the condition.

Down syndrome is a genetic condition causing babies to be born with an extra copy of chromosome 21. That additional copy changes the typical development of the brain and the body, causing some level of learning disability and a particular range of physical characteristics. The effect is usually mild to moderate, and those with Down Syndrome can lead happy and productive lives – going to school, participating in family and community activities, and holding jobs.

Although the condition continues throughout a person’s life span, children and adults with Down Syndrome can improve their ability to perform movement activities and everyday tasks with the help of physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals.

Three types of genetic variation can cause Down syndrome:

- Trisomy 21 – This is when all the cells in the body have an extra chromosome 21. About 94% of people with Down syndrome have this type.

- Translocation – This is when extra chromosome 21 material is attached to another chromosome. Around 4% of people with Down syndrome have this type.

- Mosaic – This is when only some of the cells have extra chromosome 21 material. About two per cent of people with Down syndrome have this type.

The type of genetic variation that children experience does not significantly alter the effects of Down syndrome. However, individuals with mosaic Down syndrome appear to experience less delay with some aspects of their development.

How Down syndrome may affect your child’s development

Children with Down syndrome are all individuals. The only thing they all have in common is that they have extra chromosome 21 genes. The effect that this extra genetic material has on each child’s health and development varies a lot – all have some additional needs, but the pattern of impact is different for each child.

Children and young people with Down syndrome share some common physical characteristics, but they do not all look the same. Your child’s personality is also unique. They may be sociable or shy, calm or anxious, easy to manage or difficult to manage – just like other children.

Children and young people with Down syndrome also vary significantly in the progress they make with walking, talking, learning at school and moving towards living independently. Some children and young people have a greater degree of disability and more needs than others, however good their family care, therapy and education. No one is to blame for this variation – least of all you, as a parent / carer.

Your child’s developmental needs

All children and young people with Down syndrome experience some degree of learning disability. They usually make progress in most areas, but at a slower pace. Some aspects of development progress faster than others. What’s important is that your child moves forward at their own pace – not how fast this happens.

There are recurring patterns in the development of children with Down syndrome when they are considered as a group, often called a ‘developmental profile’ of characteristic strengths and weaknesses associated with the syndrome.

Characteristic strengths:

- Social interaction – Most children with Down syndrome enjoy and learn from social interaction with family and friends. As time goes by, they often have good social and emotional understanding, and most are able to develop age-appropriate behaviour, if this is encouraged and expected.

- Visual learning – Children and young people with Down syndrome generally learn visually. This means that they learn best from watching and copying other people, and may find it easier to take in information if it is presented with the support of pictures, gestures, objects and written words.

- Gesture and mime – Children with the syndrome are often particularly good at using their hands, faces and bodies to communicate. They often enjoy drama and movement as they get older.

- Reading ability – Reading is often a strength, possibly because it builds on visual learning skills.

Characteristic weaknesses:

- Hearing and vision – Hearing difficulties are common and can contribute to speech and language difficulties. Similarly, problems with vision are also relatively common, and these can affect the ability to learn visually. However, both hearing and vision difficulties can usually be treated.

- Learning to move – The skills needed to move around and explore tend to be delayed compared with other children. However, over time many children and young people develop good motor skills and can become good at all types of sports.

- Learning from listening – Children and young people with Down syndrome tend to find learning by listening difficult. This may be because they have a hearing impairment or because language is developing slowly. It also reflects particular problems with short- term memory, also known as working memory.

- Number skills – Many children with Down syndrome experience difficulties with number skills and learning to calculate.

- Learning to talk – Many children with Down syndrome experience significant delay learning to talk. Most children and young people learn to talk, but it takes longer.

There seem to be three main reasons for this:

- It takes them longer to learn to control their tongue, lips and face muscles.

- They have more difficulty remembering spoken words.

- They often have hearing difficulties, making it hard to pick up speech.

Mosaic Down syndrome

Children and young people with mosaic Down Syndrome may be less delayed in some areas of development, but still seem to experience a similar profile of strengths and weaknesses.

How can you help your child to develop and achieve their potential?

At the present time, there is no ‘treatment’ to reverse the effects of the extra genetic material that causes Down syndrome. However, research over the past 25 years has taught us a great deal about how the syndrome affects individuals and about how to promote development.

Children and young people achieve their potential with:

- Effective healthcare

- Good parenting skills

- Everyday family activities

- Early intervention in their first years of life to support development

- Good education at primary school, secondary school and in further education

- Sports, recreation and community activities

- Vocational training and work

Conditions Associated with Down Syndrome

In addition to intellectual and developmental disabilities, children with Down syndrome are at an increased risk of certain health problems. However, each individual with Down syndrome is different, and not every person will have serious health problems. Many of these associated conditions can be treated with medication, surgery, or other interventions.

Some of the conditions that occur more often among children with Down syndrome include:

- Heart defects. Almost one-half of babies with Down syndrome have congenital heart disease (CHD), the most common type of birth defect.

- Vision problems. More than half of children with Down syndrome have vision problems, including cataracts (clouding of the eye lens) that may be present at birth. Other eye problems that are more likely in children with Down syndrome are near-sightedness, “crossed” eyes, and rapid, involuntary eye movements. Glasses, surgery, or other treatments usually improve vision.

- Hearing loss. Up to three-quarters of children with Down syndrome have some hearing loss. Sometimes the hearing loss is related to structural problems with the ear. Children with Down syndrome also tend to get a lot of ear infections.

- Infections. Down syndrome often causes problems in the immune system that can make it difficult for the body to fight off infections, so even seemingly minor infections should be treated quickly and monitored continuously.

- Hypothyroidism. The thyroid is a gland that makes hormones the body uses to regulate things such as temperature and energy. Hypothyroidism, when the thyroid makes little or no thyroid hormone, occurs more often in children with Down syndrome than in children without Down syndrome. A child may have thyroid problems at birth or may develop them later, so it is important that their thyroid levels are monitored throughout life.

- Blood disorders. Children with Down syndrome are much more likely than other children to develop leukemia, which is cancer of the white blood cells. Those with Down syndrome are also more likely to have anemia (low iron in the blood) and polycythemia (high red blood cell levels), among other blood disorders.

- Hypotonia (poor muscle tone). Poor muscle tone and low strength contribute to the delay in gross motor skills that are common in children with Down syndrome. Despite these delays, children with Down syndrome can learn to participate in physical activities like other children.

- Feeding difficulties. Poor muscle tone, combined with a tendency for the tongue to stick out, can also make it difficult for an infant with Down syndrome to feed properly, regardless of whether they are breastfed or fed from a bottle. In some cases, the weak muscles can cause problems along the digestive tract, leading to various digestive problems, from difficulty swallowing to constipation.

- Problems with the upper part of the spine. Some children with Down syndrome have misshapen bones in the upper part of the spine, underneath the base of the skull. These miss-shaped bones can press on the spinal cord and increase the risk for injury. It is important to determine if these spinal problems (called atlantoaxial instability) are present before the child has any surgery because certain movements required for anesthesia or surgery could cause permanent injury. In addition, some sports have an increased risk of spinal injury, so possible precautions should be discussed with a child’s health care provider. Atlantoaxial instability can develop or worsen at any age so it is important to be aware of subtle or major changes in function in any part of the body (such as clumsiness – when walking or in hands during fine motor tasks).

- Disrupted sleep patterns and sleep disorders. Many children with Down syndrome have disrupted sleep patterns and often have obstructive sleep apnea, which causes significant pauses in breathing during sleep.

- Gum disease and dental problems. Children with Down syndrome may develop teeth more slowly than other children, develop teeth in a different order, develop fewer teeth, or have misaligned teeth compared to children who do not have Down syndrome.

- Epilepsy. Children with Down syndrome are more likely to have epilepsy, a condition characterized by seizures, than those without Down syndrome. The risk for epilepsy increases with age, but seizures usually occur either during the first 2 years of life or after the third decade of life.

- Digestive problems. Digestive problems range from structural defects in the digestive system or its organs, to problems digesting certain types of foods or food ingredients. Treatments for these problems vary based on the specific problem.

- Celiac disease. People with celiac disease experience intestinal problems when they eat gluten, a protein in wheat, barley, and rye.

- Mental health and emotional problems. Children with Down syndrome may experience behavioral and emotional problems, including anxiety, depression, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. They might also display repetitive movements, aggression, autism, psychosis, or social withdrawal. Although they are not more likely to experience these problems, they are more likely to have difficulty coping with the problems in positive ways, especially during adolescence.

Physiological and behavioural differences in children with Down Syndrome can make it difficult to assess how sick they actually are if they become unwell, so things to be aware of are:

- Poor temperature control: They may not develop a fever at all, or may be hypothermic (low temperature) instead.

- Weak immune system: Infections that usually cause only minor illnesses can be dangerous to children with Down Syndrome.

- Mottle easily: They have poor control of their circulation, and get mottled skin with temperature change.

- Co-morbidities are common: They often have other health conditions (listed above).

- Knowing what is normal for the individual child: Assessing levels of alertness, responsiveness, muscle tone etc. can all be difficult if you don’t know the individual child at baseline. Asking parents is essential as they know their child best!

- Narrow tubes and thicker mucus: They get more chest & ear infections and generally produce more snot!

- Sensory processing difficulties: This can cause a fear of new sensations and environments so take time to explain and reassure.

- Atypical presentations of serious illness: Sepsis can present atypically (different to normal presentation) e.g. chest infections/pneumonia with sepsis can present as diarrhoea and sickness.

- Altered communication strategies: Speech & language development lags behind understanding, so they often understand more than they can express. They’re often great visual learners (but have poor short-term memory and fluctuating hearing loss) so using signs, pictures and gestures can be useful. Speak slowly, clearly and maintain eye contact. Allow for sensory processing delay of several seconds so don’t hurry a reply!

Early Support and Intervention

The first years of life are a critical time in a child’s development. All young children go through the most rapid and developmentally significant changes during this time. During these early years, they achieve the basic physical, cognitive, language, social and self-help skills that lay the foundation for future progress, and these abilities are attained according to predictable developmental patterns. Children with Down syndrome typically face delays in certain areas of development, so early intervention is highly recommended. It can begin anytime after birth, but the sooner it starts, the better.

What Is Early Support and Intervention?

Early Support is a way of working, underpinned by principles that aim to improve the delivery of services for children, young people and their families. It enables services to coordinate their activity better and provide families with a single point of contact and continuity through key working.

Early intervention is a systematic program of therapy, exercises and activities designed to address developmental delays that may be experienced by children with Down syndrome or other disabilities. The goal is to enhance the development of infants and toddlers and help families understand and meet the needs of their children. The most common early intervention services for babies with Down syndrome are physiotherapy, speech and language therapy, and occupational therapy.

How Can Early Intervention Benefit a Baby with Down Syndrome?

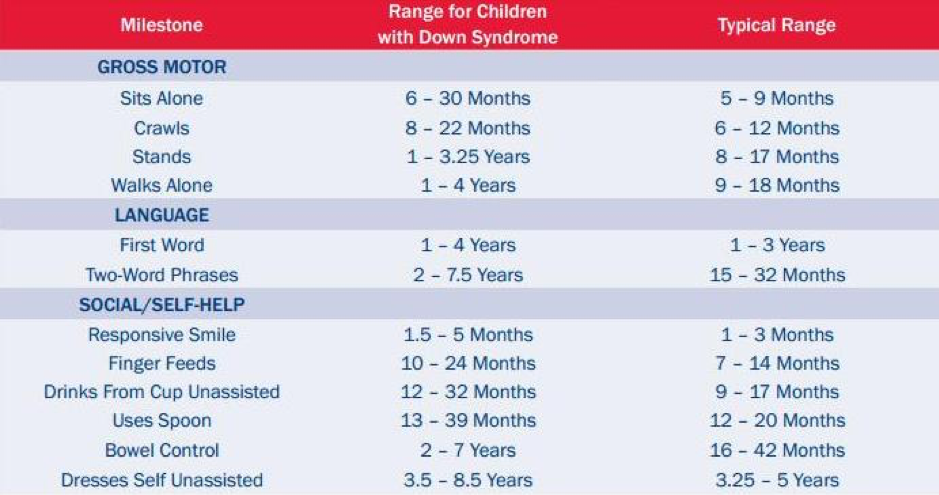

Development is a continuous process that begins at conception and proceeds stage by stage in an orderly sequence. There are specific milestones in each of the four areas of development (gross and fine motor abilities, language skills, social development and self-help skills) that serve as prerequisites for the stages that follow. Most children are expected to achieve each milestone at a designated time, also referred to as a “key age,” which can be calculated in terms of weeks, months or years. Because of specific challenges associated with Down syndrome, babies will likely experience delays in certain areas of development. However, they will achieve all of the same milestones as other children, just on their own timetable. In monitoring the development of a child with Down syndrome, it is more useful to look at the sequence of milestones achieved, rather than the age at which the milestone is reached.

The table below gives a guide of when a child with Down Syndrome is likely to achieve their developmental milestones compared to a typically developing child. It is important to note that every child is individual and there will be a large variance in this whether they have Down Syndrome or not.

Early intervention can also prevent a child with Down syndrome from reaching a plateau at some point in development. The overarching goal of early intervention programs is to enhance and accelerate development by building on a child’s strengths and by strengthening those skills that are weaker in all areas of development.

Programs of early intervention have a great deal to offer to parents in terms of support, encouragement and information. The programs teach parents how to interact with their infant or toddler, how to meet their child’s specific needs and how to enhance development.

Learning through play

All children learn through play and exploration. Children with Down syndrome learn in the same way as other children, but often benefit from more support with their play.

Here are some practical tips to support your child to learn through play:

- Become your child’s ‘play partner’. Show them how to play with their toys – what a toy does, how to get it to make a noise or to move, how to hide and find a toy, how to screw or unscrew it, etc.

- Notice what interests your child, follow their interest and copy their play. Allow them lots of practice at each stage of play by playing in ways that interest them as they need to do this to learn.

- As well as playing in ways that interest your child, demonstrate how to do more interesting things with toys. This will help your child to progress when they are ready and it can prevent them getting stuck on repetitive patterns of play.

- Take turns with your child to demonstrate how to do something. Sometimes it’s helpful to have two toys so that, for example, you can both shake a rattle, roll a ball, push a toy car or cuddle teddy.

- Later on, join in with pretend play to show your child what to do. Help them to build a sequence of two or more actions in their play. For example:

– put a toy man (‘daddy’) in the car and then push the car– give dolly (‘baby’) a drink and then put dolly to bed.

– ‘feed’ a toy farm animal and then make him run or jump. - Pretend games provide valuable opportunities to teach new language to children. Help your child to link two or three words together by saying, for example, ‘Can you wash dolly’s face?’ or, ‘Watch me put dolly in the bath.’

- Use structured play. Children with Down syndrome usually need more repetition than other children before they are able to remember and master a task. Your child will benefit if you break down tasks and games into small steps and show them how to complete each step.

- Use imitation as much as possible. Children with Down syndrome tend to be good at learning by imitating or copying other people.

- Praise your child and avoid frustration by making sure that most of the time your child gets satisfaction from playing and from toys. It can be very frustrating trying to do things that are beyond your ability. Your child is likely to experience this when they try to play with toys that need precise finger movements – they may express frustration by throwing or banging. When a young child gets frustrated, it can be quite hard for them to get over it. Music, holding hands and jigging or dancing are good ways of getting over upsets.

How can physiotherapy help my child?

Physiotherapy focuses on motor development. For example, during the first three to four months of life, an infant is expected to gain head control and the ability to pull to a sitting position (with help) with no head lags and enough strength in the upper body to maintain an upright posture. Appropriate physiotherapy may assist a baby with Down syndrome, who may have low muscle tone, in achieving this milestone.

Before birth and in the first months of life, physical development remains the underlying foundation for all future progress. Babies learn through interaction with their environment. Therefore in order to learn, an infant must have the ability to move freely and purposefully. An infant’s ability to explore his or her surroundings, reach and grasp toys, turn his or her head head while watching a moving object, roll over and crawl are all dependent upon gross as well as fine motor development. These physical, interactive activities require understanding and mastery of the environment, stimulating cognitive, language and social development.

Children with Down syndrome want to do what all children want to do: they want to sit, crawl, walk, explore their environment, and interact with the people around them. To do that, they need to develop their gross motor skills. Because of certain physical characteristics, which include hypotonia (low muscle tone), ligamentous laxity (looseness of the ligaments that causes increased flexibility in the joints) and decreased strength, children with Down syndrome don’t develop motor skills in the same way that the typically-developing child does. They find ways to compensate for the differences in their physical make-up, and some of the compensations can lead to long-term complications, such as pain in the feet or the development of an inefficient walking pattern.

The goal of physiotherapy for these children is not to accelerate the rate of their development, as is often presumed, but to facilitate the development of optimal movement patterns. This means that over the long term, physiotherapists will aim to help the child develop good posture, proper foot alignment, an efficient walking pattern, and a good physical foundation for exercise throughout life.

Here at The Children’s Physio we are highly specialised in assessing and treating children with Down Syndrome. We can assess your child and provide individualised treatment programmes and advice to aid their development.

Remember, if you have any questions or concerns relating to your child and their development The Children’s Physio will be able to advise.